My Grandfather Liberated Dachau Concentration Camp—And Why That Matters to Me

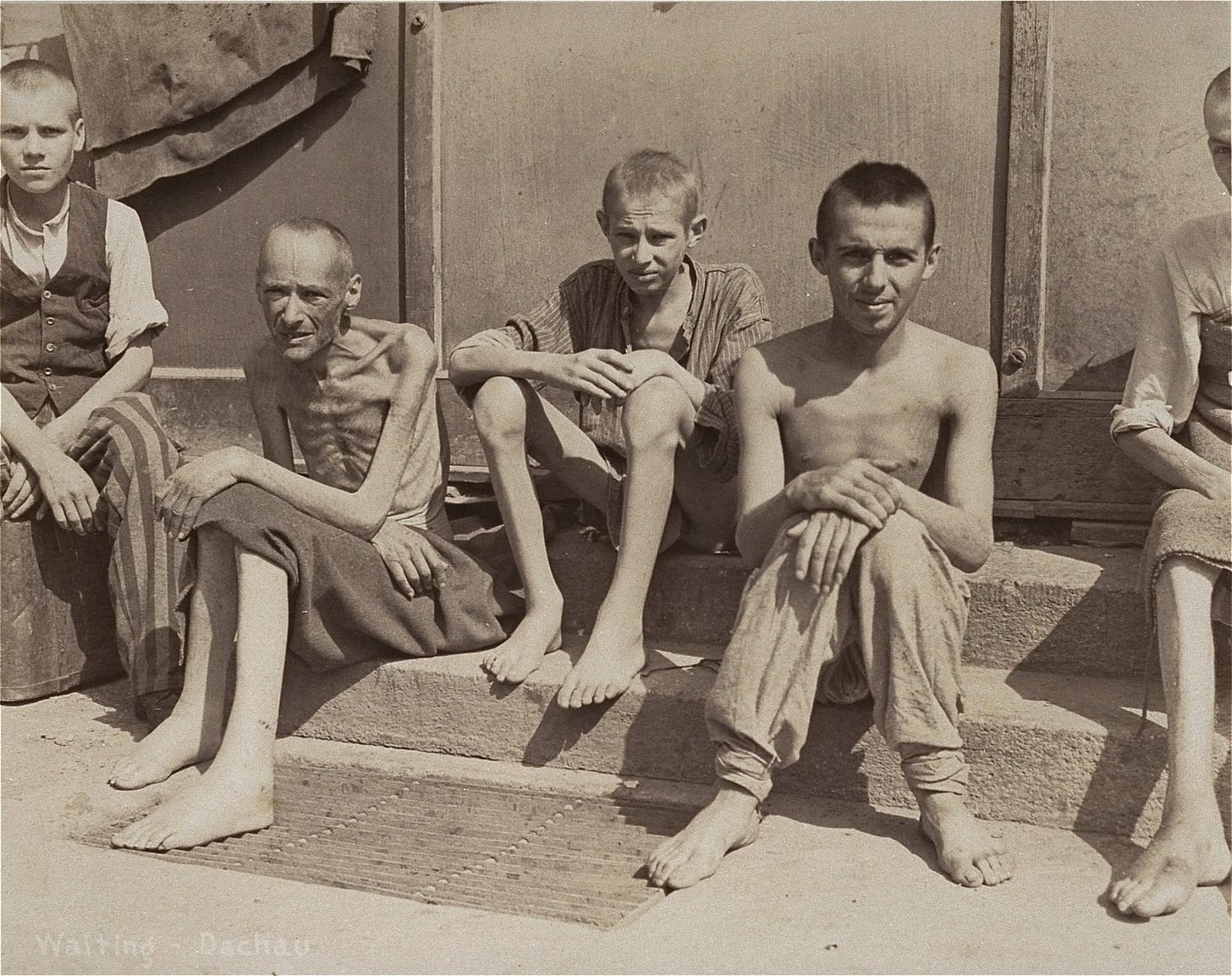

On April 29, 1945, the Dachau concentration camp was liberated by American soldiers. Situated in a picturesque Bavarian village, KZ Dachau was a grotesque horror camp, filled with tortured and starving men: Grown men weighing a mere 80 pounds, grown men huddled in corners (too weak with starvation and typhus to move), grown men accustomed but not acclimated to watching friends and fellow prisoners inhumanely die right in front of their eyes.

The Nazi brutality of WWII is incomprehensible to us as we sit in our remote place in history, reading books or even watching vintage footage showing terrifying scenes. Yet despite our abilities to empathize and feel repulsion at such immense evil, what we experience is nothing compared to those who lived it—including the soldiers on the front lines of liberation.

A stench so overwhelming it sears the nostrils with its brutal, death-laden miasma.

A surreal, apocalyptic landscape strewn with piles of naked, bony corpses.

The walking dead, skeletons with thin gray flesh, confused or begging for mercy, falling at the feet of liberating soldiers as if they were gods.

American soldiers in abject horror, frozen, uncomprehending. This can’t be so. This evil is too great … They wonder if their eyes are deceiving them. But no … There it is—the horrific evil truth of it all.

American soldiers, breathing in the foul stench, trying not to breathe, needing to breathe for others, knowing the nightmarish odor would never leave them, would cling to their skin and hair and inside their nostrils for the rest of their lives.

American soldiers, in despair and self-recrimination … Why didn’t we get here sooner? What took us so long?

Nazi SS, evil hatred still simmering in their eyes, wild and possessed, eerily void of human integrity.

But why am I writing about all this?

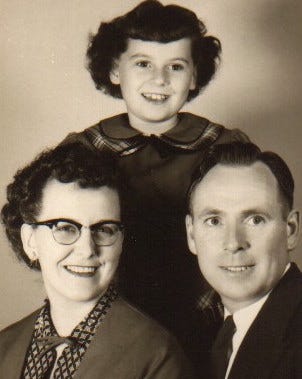

Because of my grandfather, Staff Sgt. Frederick Daley.

My Papa was the most gentle, kind, and loving man I’ve ever known. He had an undying faith in humanity and never lost that faith, hope, or love, despite all he endured.

He was the first man in his town of Stockton Springs, Maine to be drafted, entering service on February 20, 1941. Assigned to the 813th Tank Destroyer Battalion, he saw nearly every major battle—and countless terrors of war. From North Africa to Sicily, Normandy to the Battle of the Bulge, through the bomb-wrecked cities of Cologne and Frankfurt, he was there for it all.

Seeing and even engaging in such horrors was beyond traumatic, especially for such a kind-hearted and tender man as my grandfather. Yet there was one experience that exposed him to something so appalling, so ruthless, so harrowing and cold-hearted that he was barely able to speak about it after the war.

The liberation of Dachau concentration camp.

Everyone in my family knew he’d been there, but he didn’t willingly speak about his experiences. He held himself in reserve, needing to share and release, yet not wanting to burden others. It wasn’t until over fifty years later, living in the past due to Alzheimer’s, that Papa was able to relay a greater emotional depth to his stories. As he struggled through his last years, he could remember the war with clarity and precision—he just couldn’t remember his loved ones in the present.

I’ve often wondered how my grandfather could have endured such horrors, witnessed such pure evil, and still maintained his faith in humanity. After the war, due to the experience he’d gained during those years, he became a guard for the Maine State Prison. It was a tough job, to say the least—and again my grandfather was a witness to some of the most abusive personalities in the system.

How, then, had he maintained his integrity? As to be expected, the war changed him in many ways. My mother has told me that Dachau made her father less naïve about human nature, and more aware of how anger can take control of a person, turning them into someone they normally never would dream of being.

After his extreme experiences, my grandfather became extremely pro-Jewish and pro-Israel (a legacy he made sure to pass on to his children and grandchildren). He came to despise bigotry even more than he had before, simply because he’d seen more—and he’d witnessed just how destructive such attitudes could be. He hated violence, despised war, and was actually relieved that his only child was a daughter and not a son, because she could never get drafted and be forced to endure what he’d been through.

Yet my grandfather remained haunted for the rest of his life. He described Dachau as “a surreal world gone mad.” He shuddered when thinking about the loathing that filled the eyes of the SS guards—although captured they still seemed determined, within their haze of hatred, to uselessly fight on.

Despite all this, his experiences caused my Papa not to turn against God, as one might expect, but rather to move closer toward God’s embrace. He relished the beauty of the Divinely-created world, and shared that peaceful appreciation with his family. He never judged, only loved.

And forgave. My grandfather knew the art of forgiveness, and made it an active part of his life.

I’ve often admired my beloved Papa for maintaining his strength despite enduring such trauma, yet never fully understood how he could have managed to retain a positive outlook on life and a firmer faith in God.

Until I had the opportunity to visit Dachau myself.

I’ve now been there twice—during the second visit my husband and I took our four children, because we needed them to experience the intensity and enormity of the human spirit as God created it.

The first time my husband and I visited Dachau, I internally prepared myself. I was expecting to feel a pervasive sense of horror, fear, hatred, death and dread. I knew it would be a tough visit, but it was something I had to do.

Yet, as soon as I entered through the infamous Arbeit Macht Frei gate, I was overcome. Overwhelmed. Overpowered. Surrounded.

Not by hate, but by love.

Not by horror, but by peace.

While standing in the appellplatz and walking through the area where the bunkers had been, all I could feel was a deep, abiding, heart-rending awareness of prayerful peace—and a strong, insistent atmosphere of true forgiveness.

‘I forgive you,’ the once blood-soaked soil seemed to cry out.

‘I forgive you,’ breathed through the trees, whispered in the corners, wafted around everyone, everything.

I forgive you.

Jesus, I trust in you.

The only place I sensed fear was in the crematorium, but that seemed natural—and it wasn’t a resentful, hate-filled fear. It was pure, undiluted terror. But, predominately, forgiveness scented the grounds of Dachau in a way completely unexpected.

I received the distinct sense that the prisoners in this horrific camp had, as a whole, forgiven their trespassers. Despite it all. Despite the abject evil.

Perhaps this was my grandfather’s secret, too. Perhaps he’d also found a way to forgive even the most unforgivable in life.

Yet how had these men done that? How could they forgive such extreme abuse and harrowing torture?

Such deep forgiveness in the face of the worst humanity has to offer is a mystery and a grace of the Holy Trinity—and something viscerally experienced by Christ himself. I’m convinced the atmosphere I felt so strongly in Dachau was created by three simple yet complicated things:

Faith, prayers, and unity.

The Catholic Church—and, despite later rumors to the contrary, most notably Pope Pius XII—spoke out against the evils of Nazism from the very beginning, in ways both large and small. As a result, thousands of Catholic clergy were arrested and sent to KZ Dachau. There were so many priests incarcerated that at least two blocks—known as the “Priestblocks”—were set aside solely for them (Blocks 26 and 28, and for a time block 30). Amazingly, the priests were allowed an altar and were even permitted to partake of holy Eucharist.

Other clergy members were also imprisoned in Dachau, including Protestant, Greek Orthodox, and Eastern Orthodox—but 95% of the clergy were Catholic. Even so, the priests shared their prayer space, encouraging their brethren to maintain faith and love of God. They struggled and persisted in providing hope to other prisoners, especially those who were the most downtrodden.

And hope kept many of them alive.

There were relatively few Jews in Dachau in comparison to other Nazi hellholes, for the simple reason that Dachau was primarily a work camp, not a death camp. Even so, the faith of the Christian ministers, the hope and the praise of God through reciting the Psalms and other means of mutual prayer, were shared amongst their Abrahamic brethren.

I feel certain the peace that has settled within Dachau is the result of these prayers— as well as the determination to maintain hope, the presence of the True Presence, and the solidarity of prisoners who loved the same God, despite differing doctrines. The men who were brutally incarcerated inside the barbed-wire fences of Dachau were determined to join together to combat evil through praise of the One God, and that unified determination now permeates the remains of the camp. This sense of peace, and the infusion of blessed forgiveness, are graces given by God to His precious children in their time of need. They are blessings and graces which remain to this day, despite the passage of 77 years.

Sources:

Frederick Daley, personal memories as passed down to his family.

Extensive email correspondence with Bill, veteran of the 42nd “Rainbow” Infantry Division.

Jean Bernard, Priestblock 25487: A Memoir of Dachau (Zaccheus Press, 2004).

Ronald J. Rychlak, Hitler, the War, and the Pope (Our Sunday Visitor, 2010).

Brigadier General Felix L. Sparks, “Dachau and its Liberation” (157th Infantry Association).

Guillaume Zeller, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945 (Ignatius Press, 2017).

We just wrote about the Dachau memorial that says "to honor the dead, warn the living" after the NJ Appellate Division said it was inappropriate to compare the current euthanasia campaign in the USA to the Nazis: https://lifelinelegalfund.com/urgent-news