Cursing Others in Prayer: What's Up with Some of Those Psalms?

The idea of cursing others in prayer is anathema to an orthodox Christian. After all, it breaks all moral precepts. It seems wrong to ask God to take vengeance against those who’ve betrayed and wounded us. Besides, we shouldn’t even think such things—Jesus clearly told us to pray for our enemies, not curse them (Matt 5:44).

But … What about the those dark passages of the Bible, particularly the Psalms? Aren’t the Psalms our guide to prayer, filled with thanksgiving and praise, petitions and supplications, mournful longing and requests for relief from suffering?

And … Curses.

Be not silent, O God of my praise! For wicked and deceitful mouths are opened against me, speaking against me with lying tongues. In return for my life they accuse me, even though I pray for them. So they reward me evil for good, and hatred for my love.

Appoint a judge against him! Let an accuser bring him to trial. May his days be few; may another seize his goods!

May his children be fatherless, and his wife a widow! May his children wander about and beg; may they be driven out of the ruins they inhabit!

May the creditor seize all that he has; may strangers plunder the fruits of his toil! Let there be none to extend kindness to him, nor any to pity his fatherless children!

May his posterity be cut off; may his name be blotted out in the second generation! (Psalm 109:1-2, 4, 6, 8-13)

Ouch.

In 1967 Pope Paul VI took the imprecatory Psalms out of the Liturgy of the Hours, which I believe was a grievous act. Isn’t that the same as telling God there’s something embarrassing in His Sacred Scripture, something we need to avoid and pretend doesn’t exist?

The dark passages of the Bible are there for a reason, and it’s a reason we must embrace. The curses in the Psalms don’t signify God’s stamp of approval for revenge, resentment, or bitter attitudes. Rather, they show the faithful that it’s not only okay to be honest when we pray, but we must be honest—even when that honesty takes an ugly form. By telling God we’re angry at those who have slandered and abused us, and that we’re feeling an all-too-human desire for retribution, we’re purging our negative emotions by telling our Daddy God—Abba Father—exactly how we feel, and how we need to be healed.

When we release these emotions rather than keeping them pent up, we clear the space in our soul for true healing to begin. Instead of allowing resentment build until it becomes a frothing rage, if we talk to God in an authentic way about what’s bothering us—even if that conversation takes a negative form—we allow the grace of His blessings to pour through us, to renew our minds and hearts and souls. By going to God and expressing our hurt and our desire for justice, we allow the seed of forgiveness to begin to sprout. By expressing to God our every need and desire, we’re opening ourselves to receive even more of His healing graces.

It's also important to remember that these Psalms are pleas to God for His intervention in an extreme situation. These prayers aren’t about “tit-for-tat” because someone hurt our feelings or even betrayed us, but are cries of anguish in dire and severe circumstances. It’s easy to see how these Psalms would have comforted the Jewish people during the Holocaust; I can imagine that these prayers were recited as a desperate cry, a plea for justice and mercy, for an end to their excruciating and dishonourable suffering.

These Psalms aren’t prayers for revenge, but for justice and mercy.

These prayers are never addressed to the enemy themselves, but are always kept between God and the one praying. Why? Because Sacred Scripture also teaches us that this sort of extreme justice belongs to the Lord only, not to us. When our needs are brought before God, He handles them in the best way possible—for all parties involved. Through surrender to God’s will, we accept whatever comes next.

The excuse given for Pope Paul VI’s abridged breviary was that some Psalms may cause “psychological difficulty.” In fact, there are no psychological issues involved in praying the difficult Psalms if one does so with a pure heart: a heart of honesty, as well as the humility to admit even the dark side of our human selves.

This is the beauty of our Sacred Scripture. Think about it: what other religion shows such humanity in their sacred texts?

Other religions tend to gloss over our human side so as to show the “nirvana” and “enlightenment” of “what should be.” With the Judeo-Christian texts, we get the opposite: we get honesty and truth, in all our humanity.

Yes, we often fail. Yes, we sometimes harbour negative feelings toward those who have hurt us. Yes, we’re fallen and in need of God’s help. There is no “nirvana” except in the beatific vision—seeing God “face to face,” which we attain when (if) we reach Heaven.

As Msgr. Charles Pope teaches, “It’s good to recall that the overall context of prayer modeled in the Scriptures is one of frank disclosure to God of all our emotions and thoughts, even the darkest ones.” This tells us something crucial about prayer—we’re to bring all things to God, no matter how dark. When we expose our darkness to His Light, our darkness will vanish.

“The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:5)

Sacred Scripture, along with the tradition of the Catholic Church, teaches that “in praying do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do; for they think that they will be heard for their many words” (Matt 6:7). Instead, we need to be honest and forthright with God (after all, He already knows everything about us). Our prayers are conversations with Him, and should be down-to-earth, full of our true thoughts and emotions, and come from deep within the heart. No matter what we’re feeling.

It's also crucial not to interpret Sacred Scripture in isolation. The end of Psalm 109 makes it clear that justice is in the hands of our merciful God:

Help me, O LORD my God! Save me according to your merciful love!

Let them know that this is your hand. Counter their curses with your blessing.

With my mouth I will give great thanks to the LORD; I will praise Him in the midst of the throng. For He stands at the right hand of the needy, to save him from those who condemn him to death. (Ps. 109:26-31)

To again quote Msgr. Charles Pope, it’s through the dark passages of the Bible we can hear our loving Father saying to us:

I want you to speak to me and pray out of your true dispositions, even if they are dark and seemingly disrespectful. I want you to make them the subject of your prayer. I do not want phony prayers and pretense. I will listen to your darkest utterances. I will meet you there and, having heard you, will not simply give you what you ask but will certainly listen. At times, I will point to my final justice and call you to patience and warn you not to avenge yourself (Rom 12:19). At other times, I will speak as I did to Job (38-41) and rebuke your perspective in order to instruct you. Or I will warn you of the sin that underlies your anger and show you a way out, as I did with Cain (Gen 4:7) and Jonah (4:11). At still other times I will just listen quietly, realizing that your storm passes as you speak to me honestly. But I am your Father. I love you and I want you to pray to me in your anger, sorrow, and indignation. I will not leave you uninstructed and thereby uncounseled.

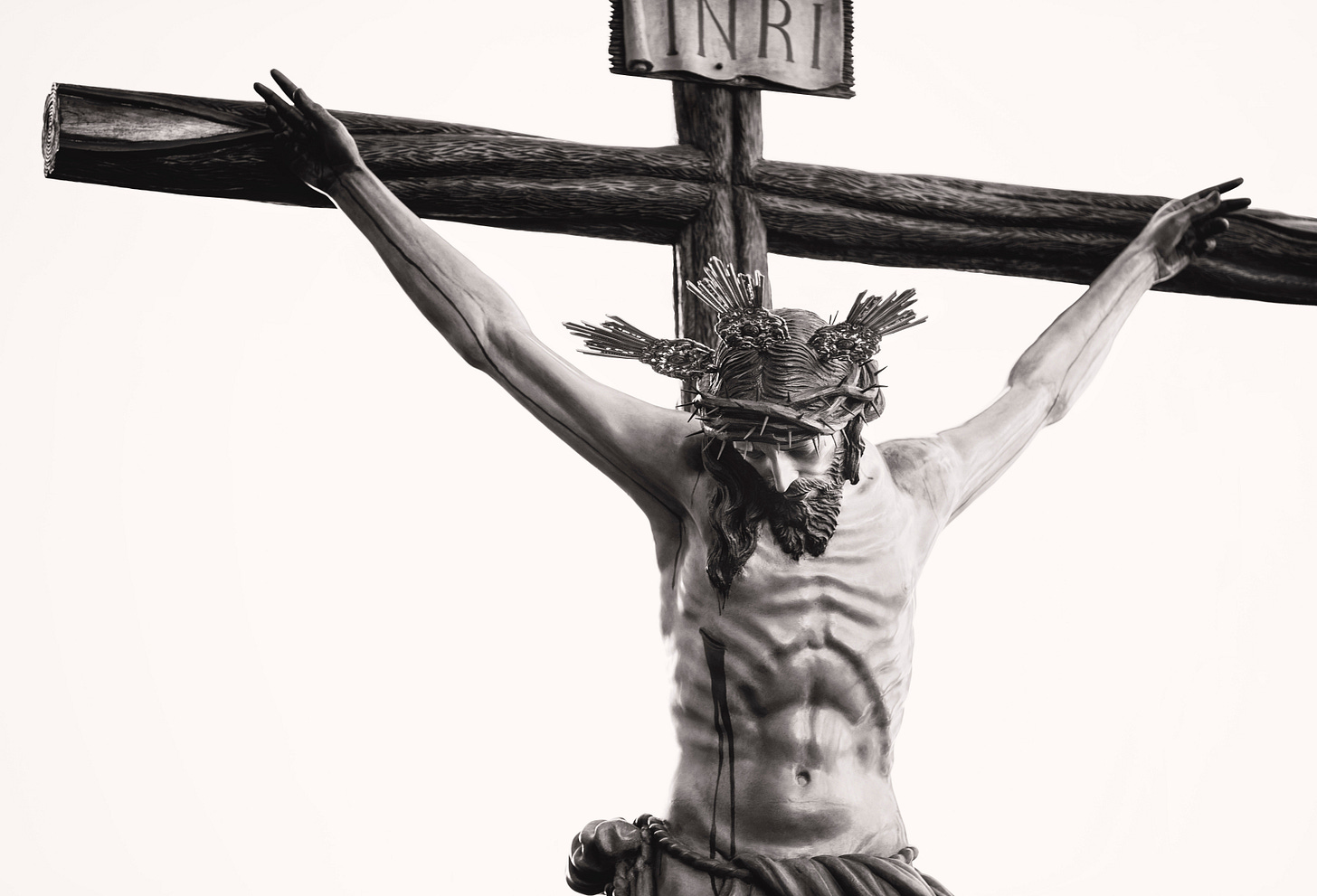

Thank you for tackling this very difficult part of the Psalms. Many do avoid it because it doesn't seem in keeping with the usual ideas we have about Christianity. But based on my experience, it is the difficult verses that help us understand God more (and ourselves, too!). They help us to pray for guidance because it is so hard to deal with it by ourselves. These verses also serve a purpose, a very deep one. In a way, I think it was left there to help us know that God understands our humanity and our frailties. Wasn't Jesus Himself the one who asked, "My God, why have You forsaken me?"